If you visit Roppongi Hills in Tokyo, you will see the huge sculpture. At first glance, it looks like a spaceship or an alien, but when you look up between its long barbed legs, you see that it is a female spider holding eggs. The pure white eggs, protected by the abdomen and thorax, seem to symbolize the spider’s maternal nature.

The creator of this work, “Maman,” which is as large as 10 meters, is Louise Bourgeois, a French-born artist who came to the United States to work. Who is this Louise Bourgeois, and how does he create this grotesque but compassionate and deeply memorable work?

Louise Bourgeois《Maman》1999/2002 Bronze, stainless steel, and marble 9.27×8.91×10.23m

Collection: Mori Building Co. Tokyo

Loving Mother and Hating Father

Let’s follow her background at first. Louise Bourgeois was born in Paris in 1911 and grew up in a house that later served as a tapestry restoration workshop in the Paris suburb of Antony, which the Bourgeois family purchased. The property was bordered by The Bièvre River, the subject of her later book, “Ode a la Bièvre”.

The tapestries, often frayed at the feet of the woven figures and animals when they were moved. Bourgeois used to sketch embroiderers to repair such damage.

At the time of Bourgeois’ birth, her father wanted a boy and was cold toward Bourgeois, who was born as a woman. The father also allowed a nanny/teacher, who was only seven years older than Bourgeois, to live in the house as his mistress, and the mother, whom Bourgeois loved, accepted the distorted relationship. Her mother died suddenly when Bourgeois was 20 years old, and Bourgeois was driven to the point of attempting suicide, giving up mathematics, which she had studied until then, and turning to art.

Bourgeois then married art historian Robert Goldwater and moved to New York City, where she raised her children and worked as a creative artist and art school teacher. After a gap and period of lack of recognition following the death of her father, Bourgeois came to widespread attention in 1982 when the Museum of Modern Art in New York held the first major retrospective of female sculptors, at the time she was 71 years old. Her creative energy did not wane, and she continued to work in her studio, a former sewing factory, and was in her 80s when she unveiled “Maman”.

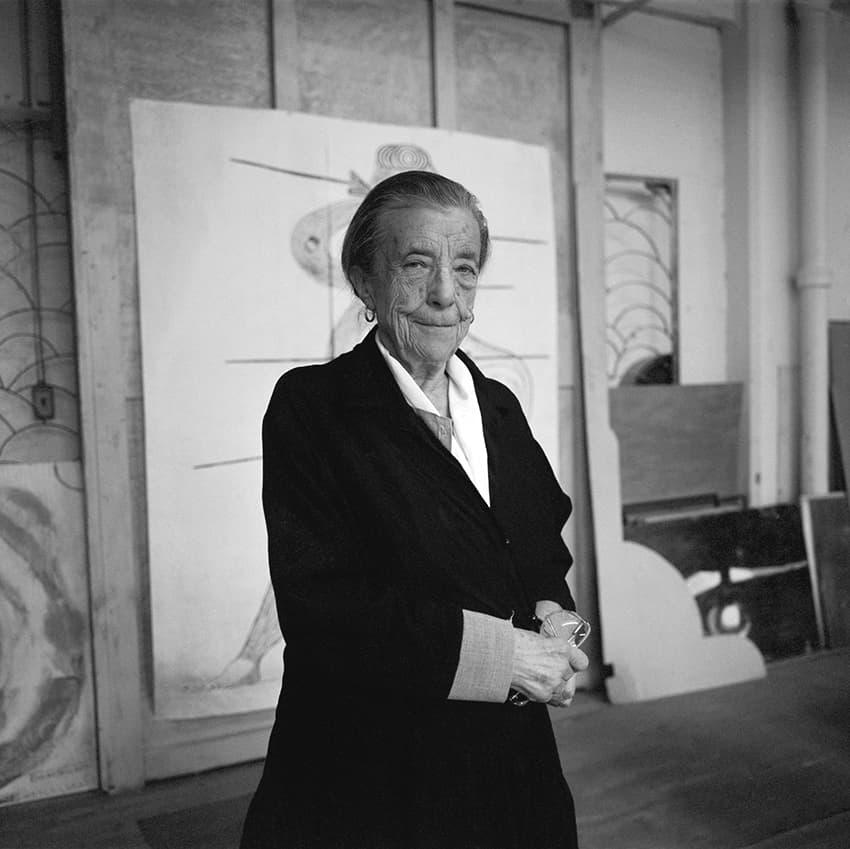

Photo:Philipp Hugues Bonan Photo courtesy: The Easton Foundation, New York

Louise Bourgeois. In front of her print “Sainte Sebastienne”.

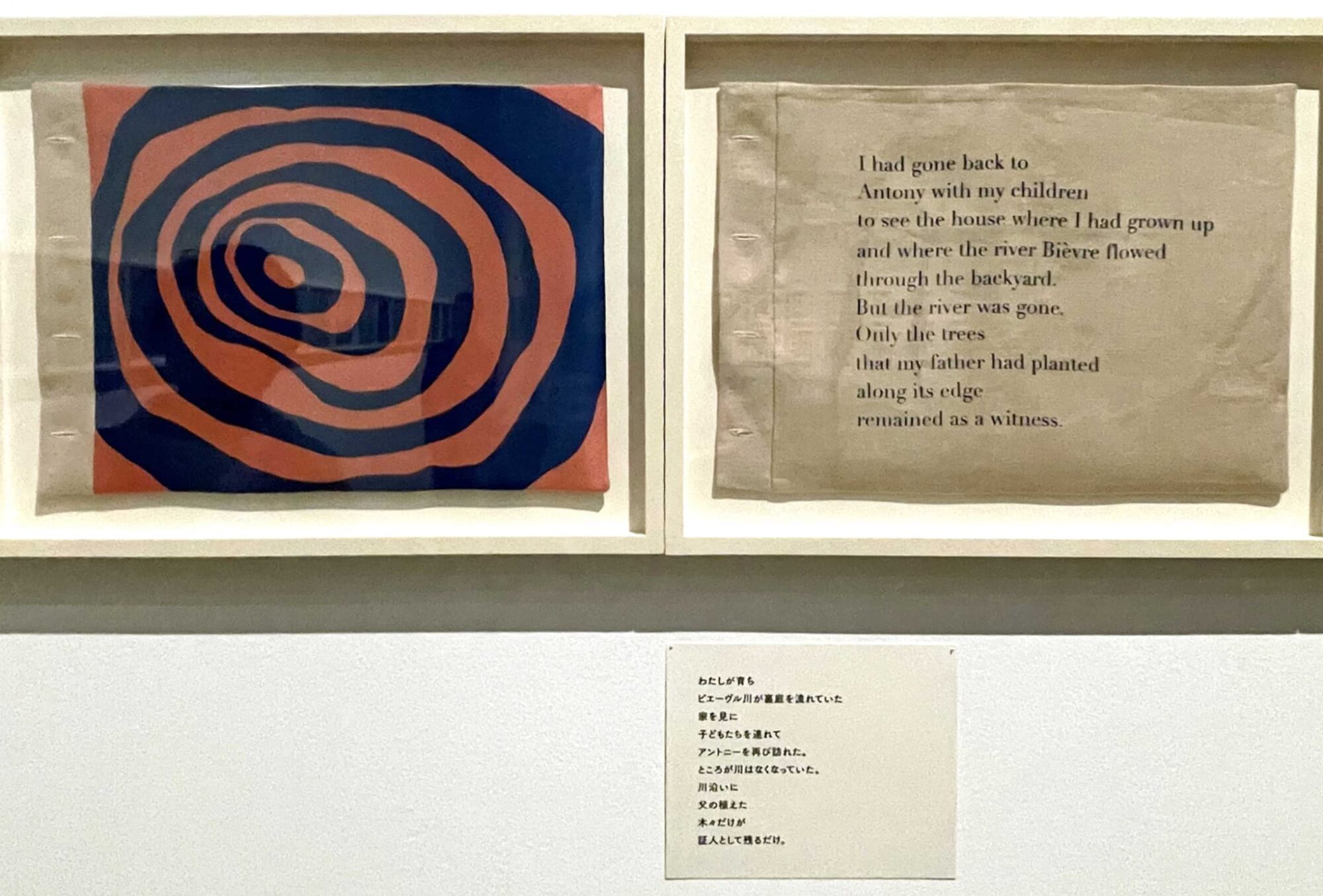

Louise Bourgeois《Ode a la Bièvre》2007 Art book(fabric, digital print, and screen print)29.2×38.1 cm(25pages)private collection(New York City)

A tribute to The Bièvre River, which flows through the grounds of her birthplace. It is said that the water of this river was suitable for fixing the dye for the tapestry. Throughout her life, Bourgeois expressed her past in images and words.

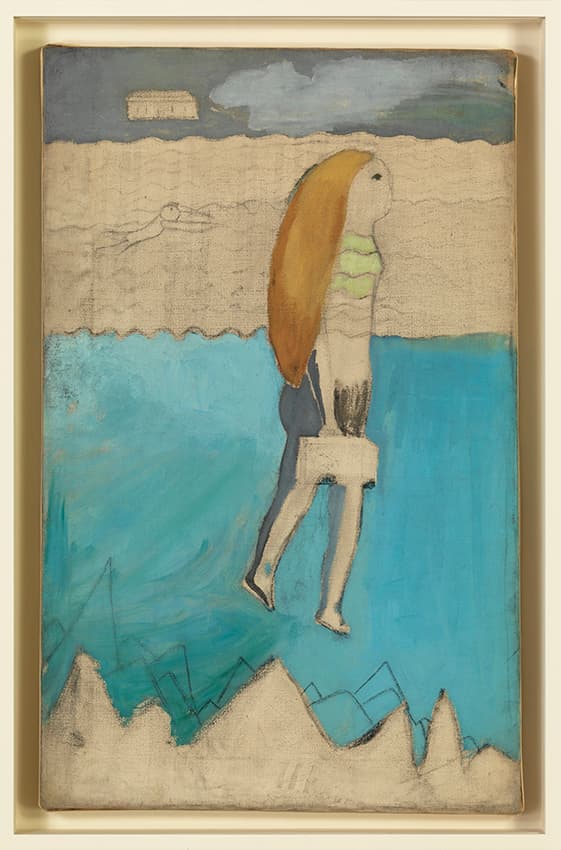

Louise Bourgeois《Runaway Girl》1938 oil, charcoal, pencil, and canvas 61×38.1cm

Photo:Christopher Burke ©The Easton Foundation/Licensed by JASPAR and VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS),

This could be the self-portrait of herself leaving New York. Bourgeois married Robert Goldwater in 1938.

various creations of Bourgeois

Her creations were diverse, including paintings, sculptures, videos, and installations. Today, it is quite common for artists to work with a wide variety of materials and techniques, but in her time, most artists continued to work in a single field, such as painters working in painting and sculptors working in sculpture. she, on the other hand, could create works that gave different impressions depending on the method of expression, such as fabric or metal, even if the shapes were similar, and could choose the most appropriate technique to suit the theme.

Louise Bourgeois《The Reticent Child》2003 fabric, marble, stainless steel, and aluminum 182.9×284.5×91.4 cm

Collection: The Easton Foundation (New York)

This work is based on the theme of Alain, the third son. Suitable materials were chosen for the three-dimensional objects arranged as if inside a theater.

One of her best-known works is the installation “Destruction of the Father. In the reddish-black lighting, there is what appears to be an altar or dining table, with objects scattered around the top that resemble pieces of meat or internal organs. The installation, which gives the impression of a grotesquely abstracted and sculpted version of Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper,” is based on a childhood fantasy of a bourgeois mother and child eating their father, who is having a long talk at dinner.

The work, made from a diverse selection of materials including resin, wood, and fabric, shows the results of her abstract figurative expression in plaster and rubber.

Louise Bourgeois《Destruction of the Father》1974 Archival polyurethane resin, wood, fabric, and lighting 237.8×362.3×248.6cm Collection: Glenstone Art Museum, Potomac, MD, USA (reproduced for exhibition, 2017)

Photo:Ron Amstutz ©The Easton Foundation/Licensed by JASPAR and VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Bourgeois was aware that her feelings for her father bound her, and through her work she attempted to break the love-hate relationship by destroying him and taking him into her body.

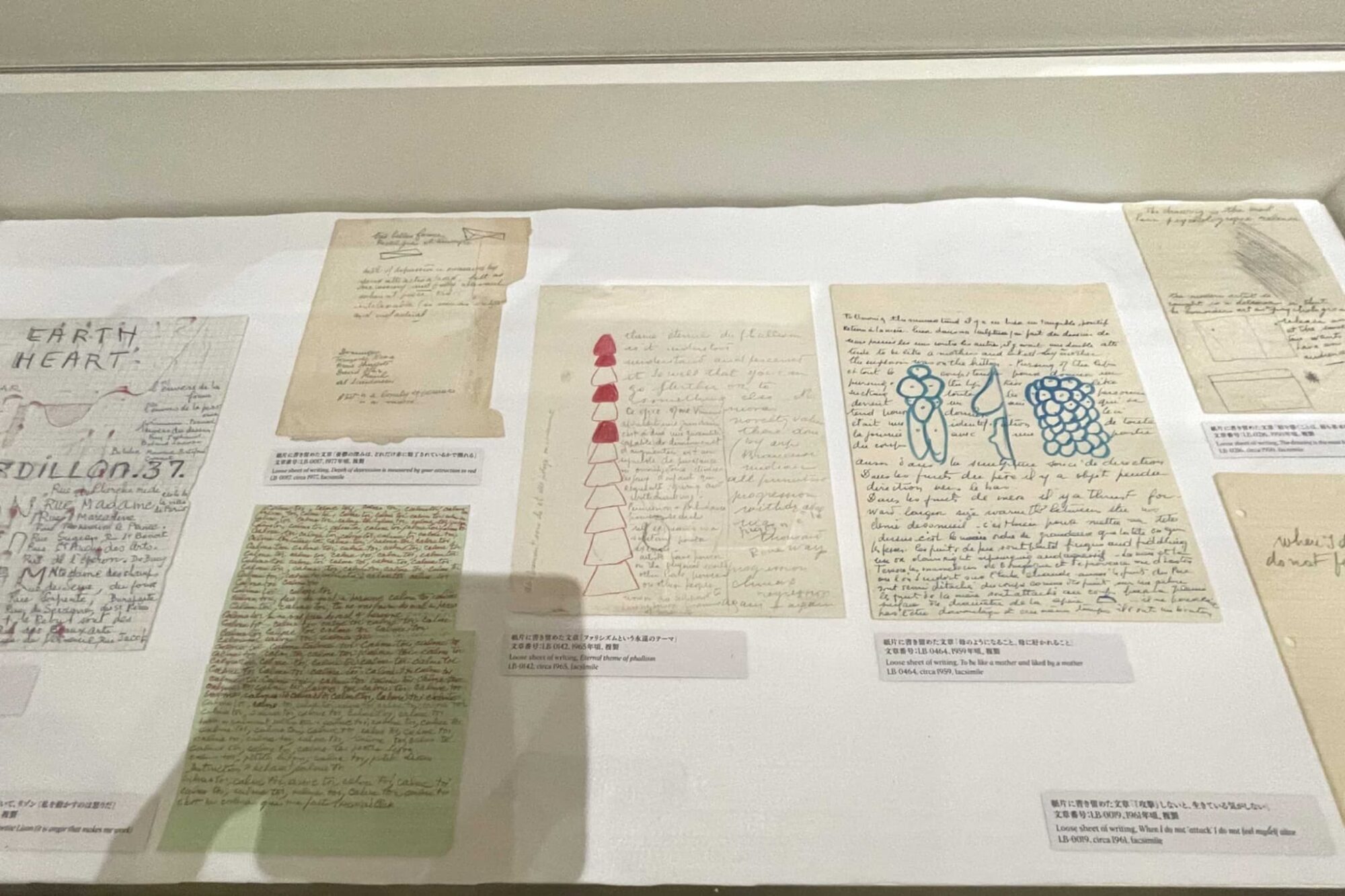

She was also an excellent writer: after her father passed away in 1951, she went to see her doctor, reading books on psychoanalysis, and kept a record of the treatments she received. Even today, she has left behind a bundle of papers that spell out her treatments, dreams, and notes with fragments of memories. The act of verbalizing and preserving her feelings and memories is strongly connected to her creations, and her sharp, painful, and sometimes black humor-tinged words help viewers to understand her works.

Despite the variety of materials and methods of expression, Bourgeois’s theme when creating her works was her own life, and her creations were intended to heal the wounds of her girlhood. From the writings she left behind, we can see that she was aware of the unreasonableness of her environment, and that her pain and obsession were the source of her creativity and the brightness of her works.

Notes and illustrations scribbled by Bourgeois. They seem to convey the source of her desire to create.

left: Louise Bourgeois《Arch of Hysteria》1993 Patina, bronze 83.8×101.6×58.4cm

Photo:Christopher Burke ©The Easton Foundation/Licensed by JASPAR and VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), Sculpture on the theme of New York hysteria. This work shows the liberation of a mental state by warping the male body, blowing away the stereotype that hysteria is a female thing.

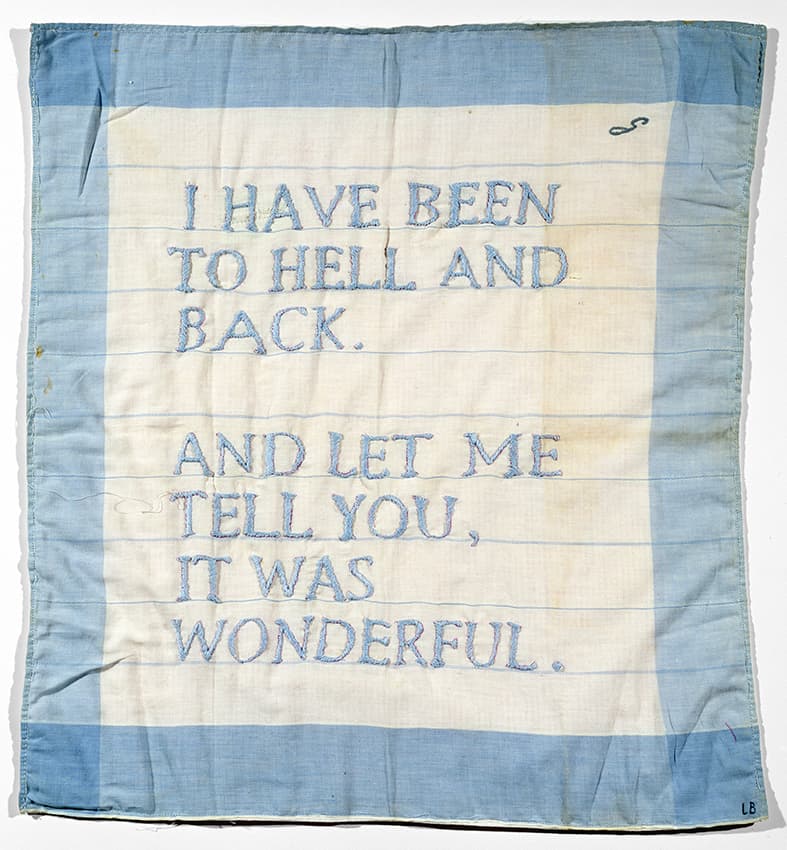

right: Louise Bourgeois《No title(I have been to hell and back. And let me tell you it was wonderful. )》1996 Embroidery, handkerchief

49.5×45.7cm

Photo:Christopher Burke ©The Easton Foundation/Licensed by JASPAR and VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Words written in a diary dated February 12, 1992, were embroidered on the handkerchief belonging to her husband Robert Goldwater, who died in 1973. The way in which loss and loneliness are transformed into black humor and then sublimated as art shows a sense of Bourgeois.

Going back to the Tapestry Restoration Factory

Bourgeois, who had a free use of materials, made extensive use of textiles and fabrics in her creations, which can be attributed to her family’s history as a tapestry restoration factory.

Here are some myths and legends about fabrics. In Greek mythology, Theseus escapes from the labyrinth with a ball of thread given to him by his lover Ariadne. In the same myth, Penelope weaves and unweaves the coffin robe of her husband Laertes to bury him and fend off suitors. In Christian stories, cloth is often an important motif, most notably in the well-known episode in which Christ wiped the sweat from his face with the veil offered to Veronica, and the image of his face was transferred onto the fabric.

The needle can be seen as a tool to attack the enemy while mending something. The thread functions as a way through the labyrinth that is life, and as something to unravel. A cloth made with a needle and thread can be thought of as marking the boundary between life and death.

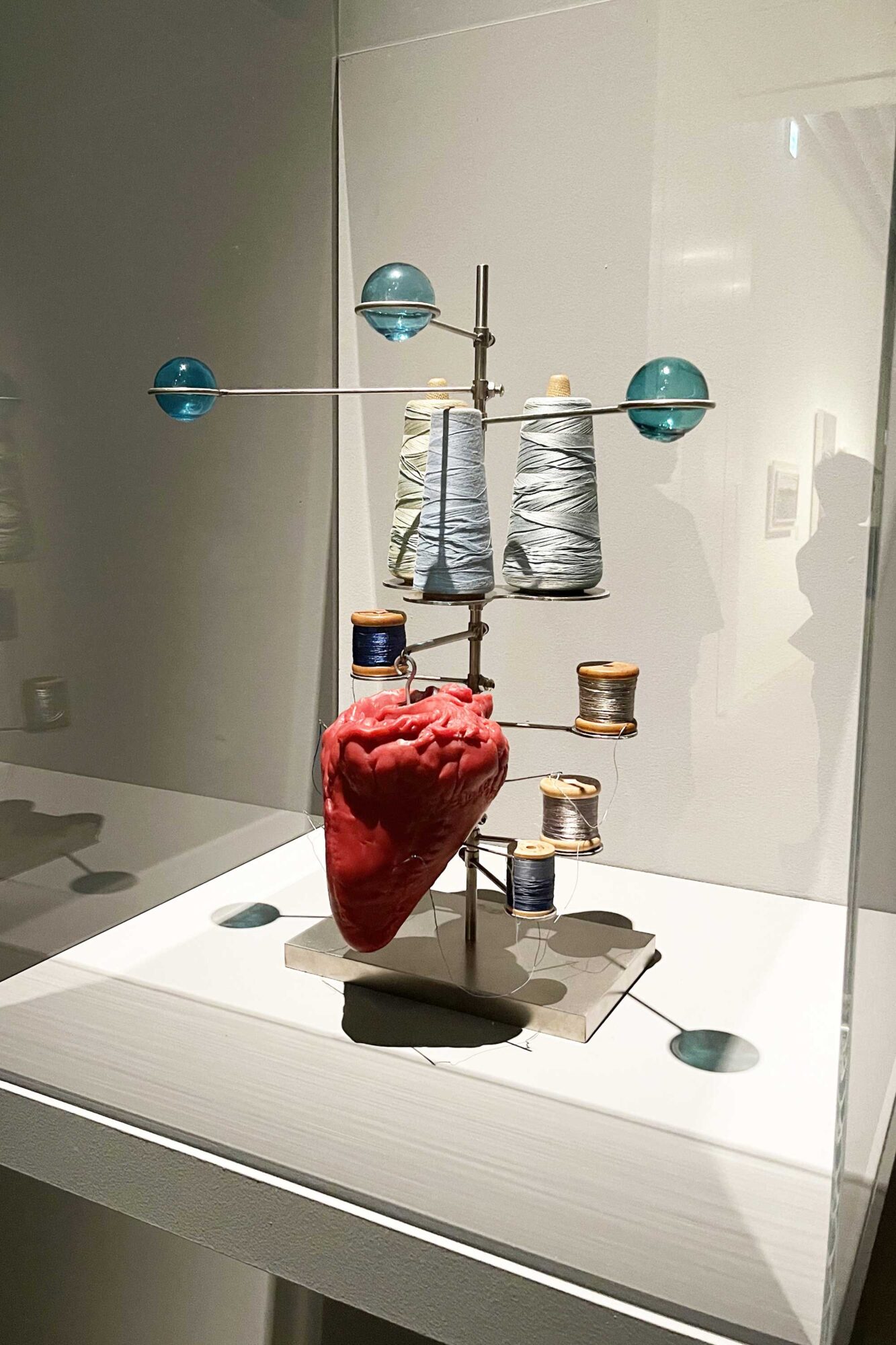

Louise Bourgeois “HEART” (2004) rubber, stainless steel, metal, thread, plastic, wood, cardboard 59.1 x 48.3 x 29.2 cm, Collection: The Easton Foundation, New York

A needle is stuck into a red heart. Will the thread being pulled out from the spool of thread repair the heart, or will it be sewn into a cancerous knot?

As seen in the Japanese folk tale of the crane weaving fabric and the Chinese Tanabata legend of the weaver princess weaving, many of the weavers of fabrics are women, who are both injured by fabrics and at the same time establish their identity. This can be linked to the fact that Bourgeois, who was subjected to cruel words from her father because she was a woman, and whose reputation was delayed by the male-centered art world, also found pain and suffering to be a source of creativity and restored herself by using a needle and thread as a weapon.

As a child, Bourgeois sketched damaged legs for tapestries. The process of repairing a damaged body is probably woven into her creative act. Tapestries also often use myths and folk tales as motifs to confine their narratives. Bourgeois’s vast creations, like her woven tapestries, could be seen as containing her own world.

Louise Bourgeois, The Good Mother (detail), 2003 Cloth, thread, stainless steel, wood, glass Sculpture and stand: 109.2 x 45.7 x 38.1 cm

Photo:Christopher Burke © The Easton Foundation/Licensed by JASPAR and VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Pink fabric made mother breastfeeding on white thread. Also the number 5 indicates Bourgeois' birthplace and the number of family members after marriage.

Bourgeois’ vast and magnificent body of work can be seen in the exhibition “Louise Bourgeois: I have been to hell and back. And let me tell you it was wonderful. ” at the Mori Art Museum in Roppongi, Tokyo from September 25, 2024 (Wed) to January 19, 2025 (Sun).

Photographs without names were taken by the writer Akiko Nakano at Mori Art Museum, Tokyo.

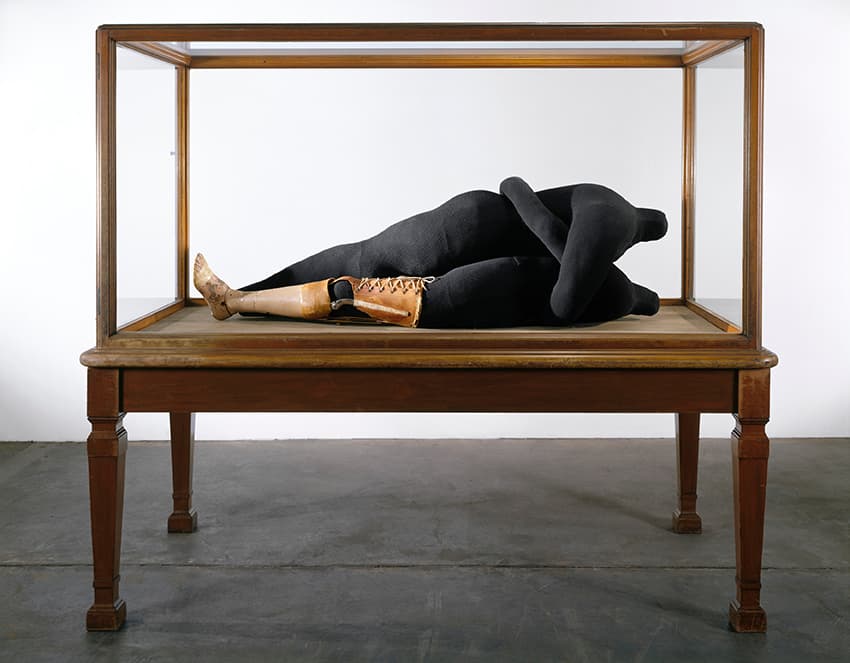

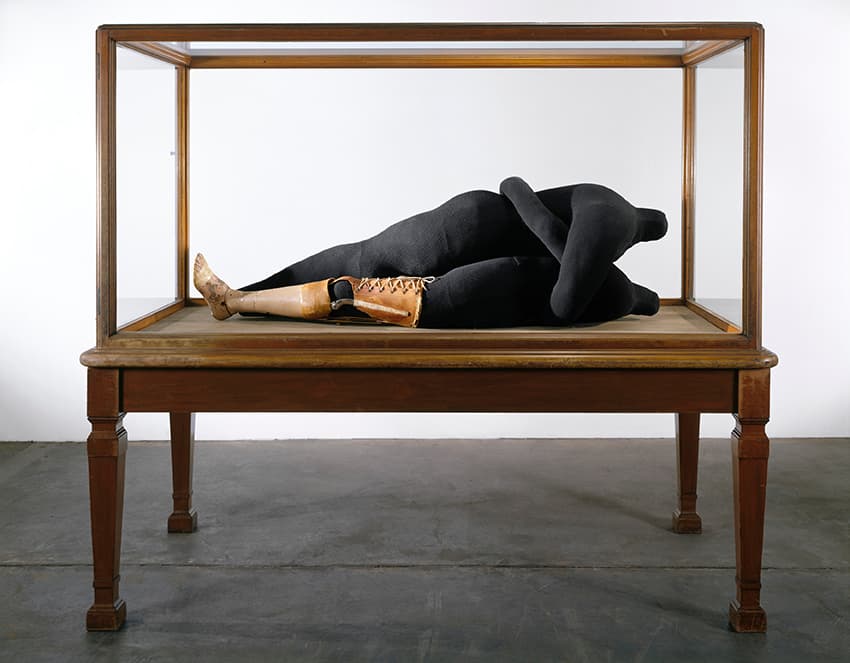

Louise Bourgeois, 《Couple IV》, 1997 Cloth, leather, stainless steel, plastic, wood, and glass

Sculpture: 50.8 x 165.1 x 77.5 cm, display case: 182.9 x 208.3 x 109.2 cm

Collection: The Easton Foundation, New York

Photo: Christopher Burke © The Easton Foundation / Licensed by JASPAR, Tokyo, and VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A couple of intertwined cloth figures are sewn together with thread, unable to move. The prosthetic device is attributed to a returning soldier witnessed after World War I. Is there a memory of sketching a damaged leg in the past mixed in with the prosthetic device?

information

Louise Bourgeois: I have been to hell and back. And let me tell you it was wonderful.

Dates: 2024.9.25 (Wed) – 2025.1.19 (Sun)

Hours: 10:00-22:00

Tuesdays only until 17:00

However, until 23:00 on September 27 (Fri.) and 28 (Sat.), 2024, until 17:00 on October 23 (Wed.), and until 22:00 on December 24 (Tue.) and December 31 (Tue.), 2024.

Last admission 30 minutes before closing time

Venue: Mori Art Museum (53F, Roppongi Hills Mori Tower)

WEBSITE

writer

Akiko Nakano

Freelance writer. On my days off, I spend most of my time in art museums, movie theaters, libraries, and bookstores. I would like to communicate more deeply about creativity in art, design, and fashion, as well as the people, things, and objects that support them, using words that convey the message.